1932 Letters

LAUREL AND HARDY LETTERHEAD - HANDWRITTEN

Hal Roach Studio,

Culver City, Calif.

Jan. 9th. '32.

Dear Friend Marion [Neal],

Please pardon delay in reply to your nice letter of Nov. 21st. Just haven't had any time for writing. Sorry I disappointed on the air when we received the award but I thought it better for "Ollie" to be the Spokesman! Glad you liked "Any Old Port." I think you will like "The Music Box." I don't care so much for "Scram," following that we have "Their First Mistake," "Towed in a Hole" and "Twice Two." The latter one, Hardy & I Play our Sisters in it - it turned out pretty good - went very well at the preview. Many thanks for the lovely Xmas card - your thoughtfulness is greatly appreciated - I was too busy to send any out this year, so don't think I had overlooked you. My kind regards & sincere good wishes for a Happy & Prosperous New Year.

By Stan’s Father

Told to the “Picturegoer” by [Arthur] Jefferson, his father, who acted Repertory with George Arliss, when the Disraeli of the talkies earned thirty shillings a week.

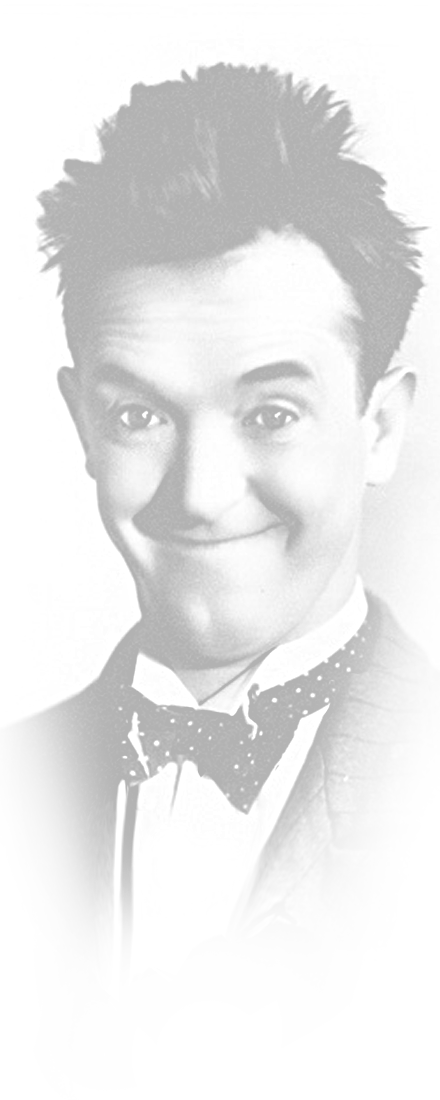

Thirty years ago a sad-eyed, brown-haired boy “played the comic” in the attic of his home at North Shields. He must have fooled delightfully before the fragments of real stage scenery that had come his way as a result of his father being a touring actor in drama. Anyway, his playmates never thought of asking for the return of the pins, cigarette cards, or marbles they had paid for admission.

Since then the price of his hire has jumped from pins to many hundreds of pounds a week—and is still soaring.

That boy was Stan Laurel, now of Laurel and Hardy fame and one of the three greatest comedians of the talkies; then, just Stanley Jefferson, schoolboy.

His father, peeping in at the attic door in those early days, was not entirely pleased with the performances he saw.

For one thing, he personally loved the drama. He lived by and for the drama. For another, he had toured the country for years in a company of Irish players with a man named George Arliss, he and Arliss taking leading parts—and what would George Arliss think of a dramatic actor’s son who had no ambitions above “playing the comic?”

Mr. Jefferson placed a lot of importance on what George would think: for they were great friends. Had they not (as a delightful letter recently received from the film Disraeli, which Laurel’s lather showed me) spent many struggling bitter-sweet years together in touring repertory. They got thirty shillings a week each “when they could get it.”

No, he used to ponder at that attic door, George would not be pleased. Nor was the tearful, plaintive comedy which Stan essayed altogether in the Jefferson tradition.

Indeed, the Jeffersons had been one of the six families that were the drama round about the 1850’s, in the heyday of the theatre. Joseph Jefferson [Stan’s grandfather] had swept through America like a whirlwind in 1858, playing Lord Dundreary there 800 times.

Stan would never sweep through modern America like a whirlwind with such fooling as this, strangely funny though it seemed.

But...never. Well, never is a long time. Who could have foreseen the talkies? Who could have foreseen that the wistful drollery of this little boy in a North Shields attic would one day hold thousands of American audiences simultaneously?

Hereabouts something big came into Stan’s young life, but he did not realise its greatness. I will let his father tell it in his own way.

“I went up to London,” he says. “And while there I met a Mr. Walter Gibbons—now Sir. And he showed me a marvelous appliance that would project living, moving pictures on to a screen.

“He called it the Randvoll and, having seen the miracles he had described to me with my own eyes, I bought it.

“And so it came about that I took the first kinema projector to the North. And did the North like it? Not a bit Not even when I put a singer at the back and tried to synchronise her with the film.

“And did Stan get excited? Not a bit. I don’t remember a single display of enthusiasm on his part.

“In that black box lay his future fortunes. And he was not even interested.

“I sold it in the end for a trifle to a man with whom I was having a drink. He started in the moving-picture business with it. Today he is a leading film magnate, but I shan’t hint at his identity, except to say that I sometimes see him arriving at his office in Wardour Street in his Rolls-Royce.”

Yes, that black box was to make rich and world-famous the little boy who was fooling upstairs in the attic. “But,” said Mr. Jefferson pathetically, “whatever it was to do for my son, it was to kill my great love, the drama.”

One morning Stan walked out ambitiously with his bag to “start touring like Dad”—but not altogether like Dad, for he went as a small-part comedian.

A few small parts in even smaller companies, a few months of struggle and bitter disillusionment, and he joined Fred Karno's company.

“You’ll be understudy to that fellow over there in the corner and do a bit of stuff yourself,” they told him.

Stan looked in the direction indicated. “That fellow over there” was another small-part comedian, but he looked very great and very important to Stan Laurel at the moment. Stan, as his understudy, was probably the only man in the world who felt that way towards him.

His name was Charles Chaplin.

The Karno company moved to America for a tour and then came back; all of it, that is, except the quaint little man named Charles Chaplin and the quaint little admirer who understudied him—perhaps the first man in the world to idolise the artist of the queer walk and the heart-breaking style of humour.

Charlie went on the films almost at once and made good. Stan, not so fortunate, went into juvenile parts on tour, and all but starved. He had years of heartbreak. But always he kept his eyes on Hollywood, until one day his chance on the films came...Only when he was doing well dare he let Charlie Chaplin know his whereabouts. Then: “Why didn’t you let me know before?” asked Charlie.

“Stan has owed much, since, to Charlie’s encouragement.” said Mr. Jefferson. “They meet, of course. And he has talked to his little understudy of Karno days as he cannot talk to anyone else about those years of struggling.”

And then, with Stan Laurel already, making his way on the films, a certain Oliver Hardy smiled his way into the picture.

Mr. Hal Roach, Stan&’s employer, told him that if he wanted to “go over as big as possible” he wanted foil, somebody who would provide a humour that would contrast with his own, and hunted out Oliver Hardy, music-hall comedian.

“He was not quite as ‘opposite’ as desired,” added Mr. Jefferson, “but Stan altered his own style drastically—and then he was.”

Just when success was coming, Stan Laurel came to England for his first holiday and told his father he was going to fly to Paris.

“You’d better make your will,” his father replied.

“And do you know,” Mr. Jefferson relates “that within three hours the London evening papers were full of the story of a crash in a French field.

“Stan did not matter to them then. He was quite unknown, of course. But I always think that if some talkie camera had got him sitting wistfully on a shattered box waiting for help to arrive, as he was when they found him, we should have got his best picture.”

Laurel is a glutton for work. He hardly ever has a holiday and, if he does, it is a short one. As he finishes one film he starts another. There are always three waiting.

But—as his biggest critic—his father has a word of advice to offer him.

“Although he is soaring in salary and popularity, I would tell you that there is much more in him than the films have brought out of him as yet. He has that humour that makes you cry. He and Charlie Chaplin alone have it—and probably it is because they have a certain similarity that they found themselves picked for the same Karno part.

“But that form of humour—which is the best, I think, humour being very near to pathos—has never been brought out fully in his films. Sometimes, sitting in the Walpole Cinema, Ealing, where I always go—and I get a cheap seat for preference because it is neat the screen and I thus get near him—I think he is going to give it.

“And then the chance goes. I feel then that I want to dash right up to the screen and say. ‘Stan, Stan...’ as if my encouragement could help him to break away from the ‘book’ a little and give us a bit more of what England wants and a little less of what America expects.

“I feel as if such a word from me would help him to say, ‘I am going to give of my best, whether you like it or lump it, and not suit my style to a particular demand’—which is real art.

“I sent him a little sketch of my own, which they filmed under the stupid title of ‘Another Fine Mess,’ and I didn’t like the American angle they got on it one bit.

“But I think he is going to get the chance to give what he wants to give, from what I can hear.”

Laurel’s mother is dead, and I asked his father why he didn’t go to Hollywood to join his son and the little family of a wife and wee daughter.

“He has asked me too, but it would mean retirement,” he said. “And I want to work again, in drama, on the real boards. Away from the footlights I feel so lonely at nights, except when I go to see Stan.”

This fine old man, who is marching toward seventy, and who bears an amazing resemblance to his son, looked unexpectedly sad as he continued.

“But what is there in drama for me now? The silent films played havoc with it. The talkies came and killed the silent; and film actors tasted the tragedy that the old dramatic actors had suffered a few years before.

“The old order changeth...What will they give us next—talkies televised direct to our fire-sides? I wonder. I wonder.”

—Picturegoer Weekly

January 9, 1932